Painting and drawing fantasy imagery is fun and creative. However, one major challenge to doing so is a lack of references. Portrait and landscape artists always have a reference to work from. Unfortunately, artists that paint fairies and dragons do not. References give an artist confidence to know that what he/she is painting will be visually convincing. Without a reference photo, how do fantasy artists pull off believable imagery?

So what do fantasy illustrators do to help them hit the mark? These artists often use the power of their own imagination in combination with numerous approximate references to develop their imagery. For example, using observable butterfly wings as fairy wings, or reimagining the components of construction equipment as robot parts.

Essentially, fantasy artists still work from references. They just do so in a more creative way.

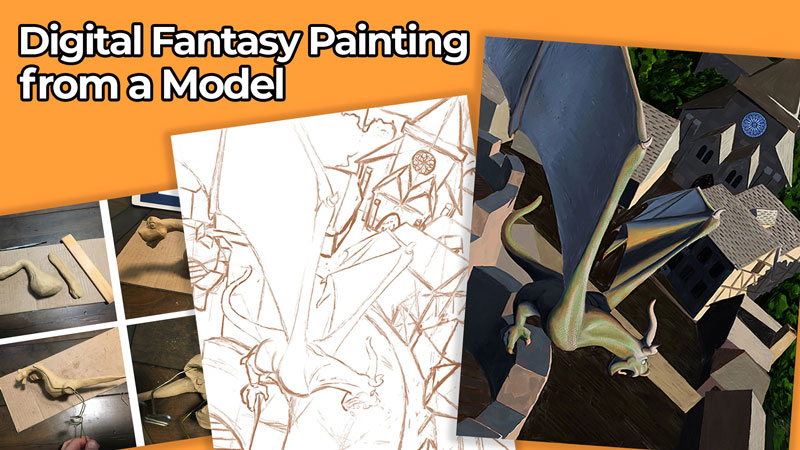

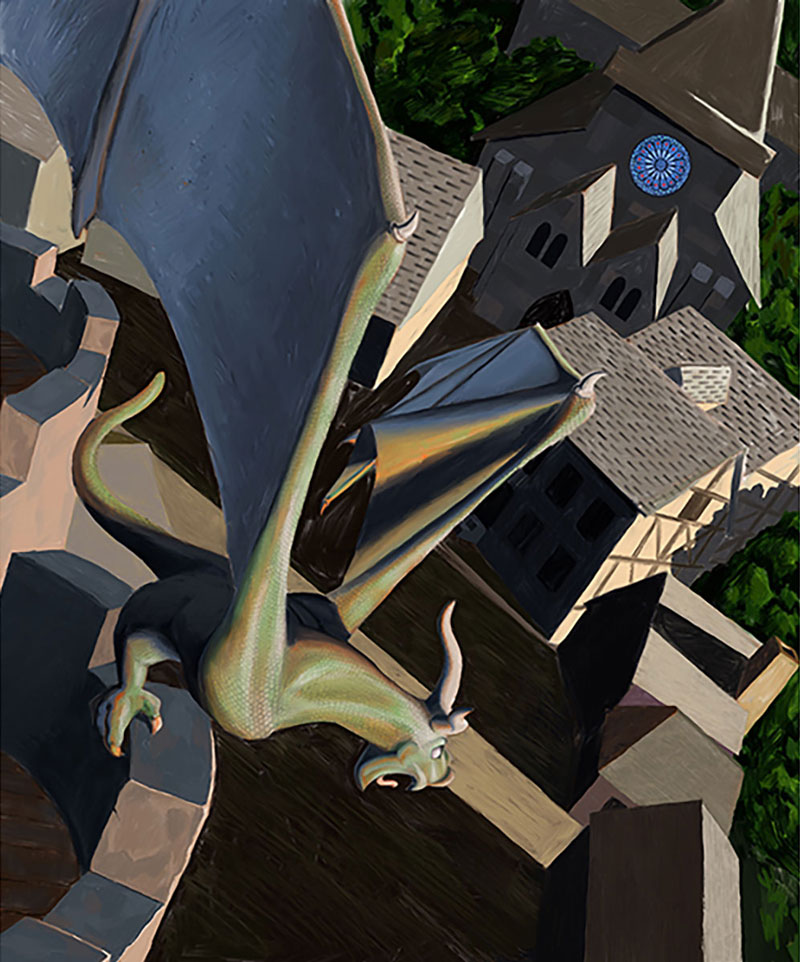

In this article, I would like to profile a process used by myself and other artists to create convincing fantasy art. This process brings together the desire to imagine with observational drawing skills. It was the process used to develop the digital fantasy painting below.

Planning a Fantasy Painting – The Art is in the Planning

Often times, the most important artistic decisions are made before a painting begins. Sometimes, numerous studies and thumbnail sketches are made to sort through compositional choices. Each sketch offers one option the artist could pursue.

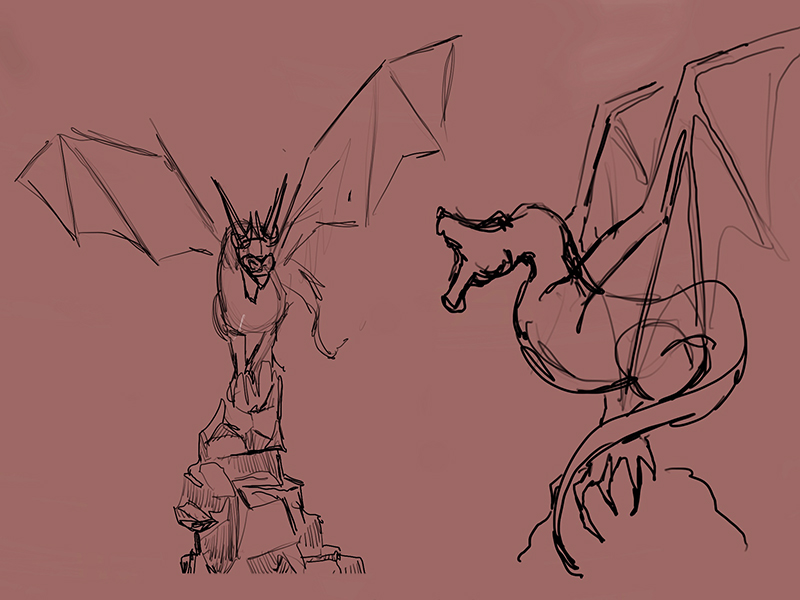

The greater the number of preliminary sketches the artist makes, the more choices they have. These sketches don’t have to be perfect – they just have to capture a generalized idea. Here’s a look at a few rough preliminary sketches of the dragon I planned on using in my scene…

As you can see, these are simply loose gestural sketches without any detail or shading.

See also: Gesture Drawing the Human Figure

Another Way to Create a Fantasy Sketch

There is another way to sketch fantasy subject matter. But instead of sketching with paper and pen or even a digital tablet, let’s sketch in three dimensions. Three-dimensional sketching gives the artist an easy way to tweak variables like point-of-view and lighting.

A two-dimensional sketch is usually a broad, loose drawing that is short on details. Often done at once, a sketch is just a step in the process of “wrapping our minds” around our subject.

It’s the same when sketching in three dimensions. A 3D sketch is not a sculpture so much as a rough model. This model gives the fantasy illustrator a better chance to accurately capture the nuance of light and to tackle difficult drawing problems like foreshortening.

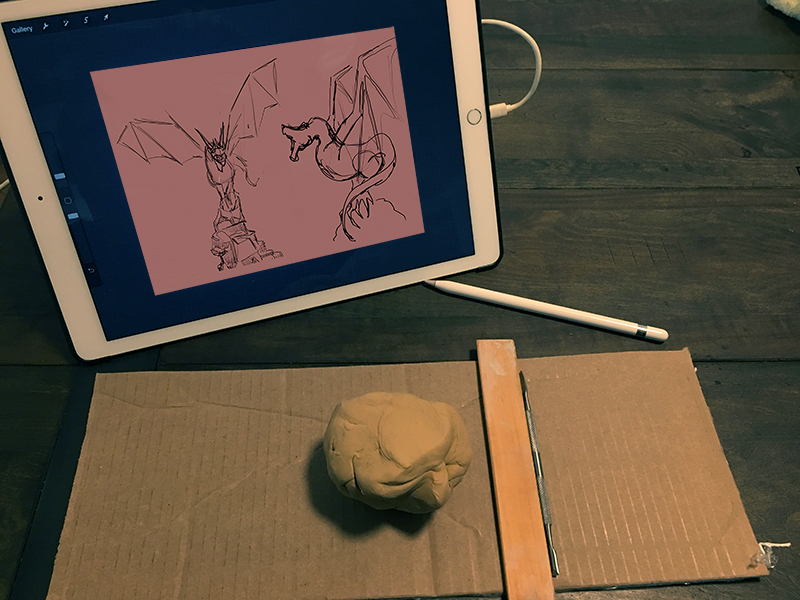

You don’t have to be an accomplished sculptor to create a workable model. Let’s take a look at how easy the model building process can be.

Building a 3D Model for Reference in a Fantasy Painting

The best media for 3D sketching are modeling clays that do not dry out when exposed to air. Plasticine is a brand of modeling clay that is made with petroleum jelly and is my top recommendation. It is a high malleable clay.

Sculpey is another brand of modeling clay that hardens when baked in a conventional oven. These two products are similar but do not feel the same. My preference is Plasticine, but I used both together to build the model below.

Besides Plasticine and Sculpey, the following materials were used to make the model…

- wire for an armature

- sculpture tools

- balsa wood strips

- drafting Mylar film

- wood glue

- a drill

- wood block for a base

Modeling clay allows the artist to focus on proportions first and the pose second. The model can be bent into position after it is assembled from basic forms. It doesn’t have to be built in its final pose. However, If the model is tall or has thin parts it could require an armature (as did the dragon). In this case, one might have to sculpt the forms and capture the desired pose all together.

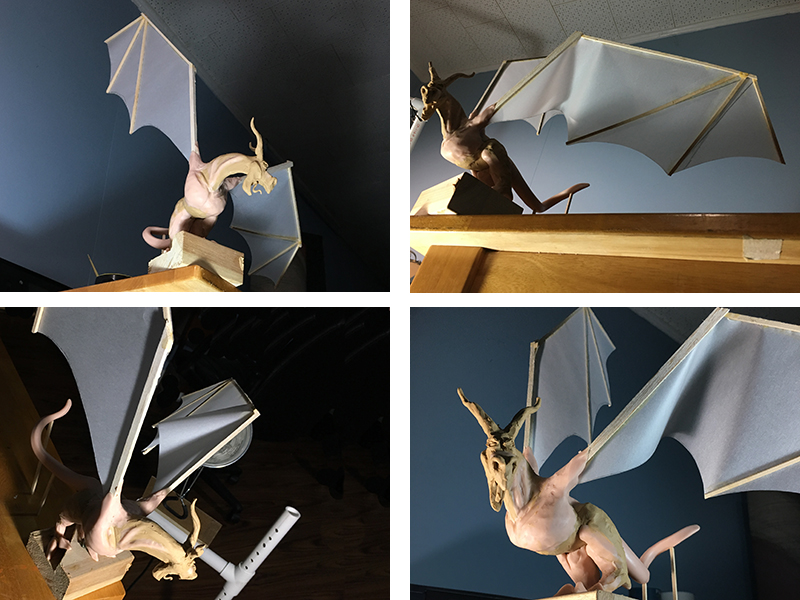

I used balsa wood and mylar to build the wings. The wood and paper wings do not unify with the clay body of the dragon but that doesn’t matter. Where the model is lacking, our imagination fills the gaps. Use any materials in combination with the modeling clay to save time and energy. You can even push objects into the clay to make textures or other unique features.

The fun begins when the model is done. It is time to play with point of view and lighting. Now, every angle from which you observe your model serves the same purpose as one two-dimensional sketch. There are literally thousands of angles to choose from. Similarly, you can quickly move a light source around a model, studying numerous options in just minutes before making a decision. Take a look at a couple of options below.

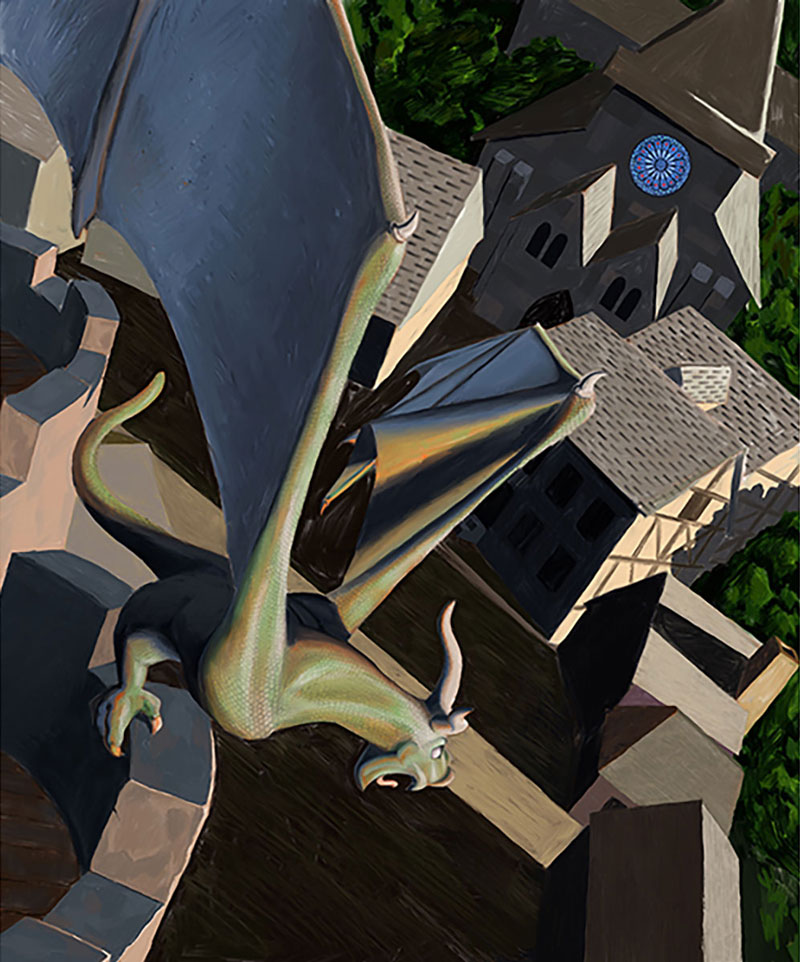

The reference photo taken from above (in the bottom left) inspired the finished painting. The extreme perspective of the light stand (white PVC in the photo) influenced the perspective of the buildings.

See also: Linear Perspective

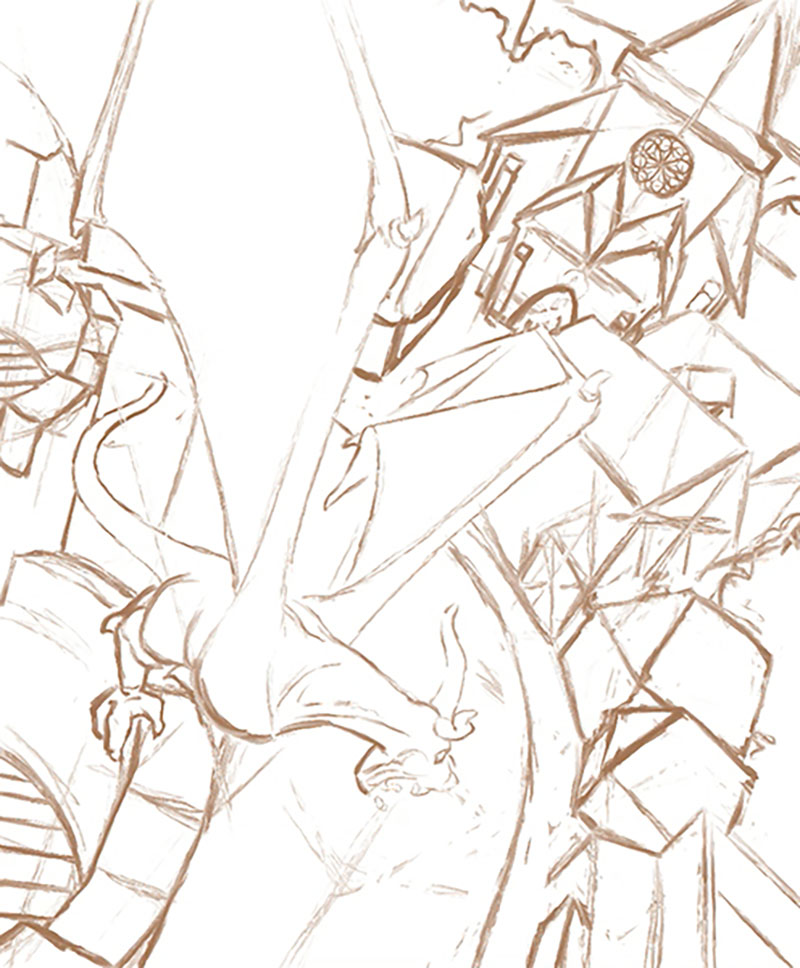

Making the Fantasy Painting

The finished painting was completed using Procreate, a digital painting program. Just like Photoshop, the program allows for the use of layers. I used the photograph of my model as a temporary layer and traced the contours of my dragon on a separate layer. If I were instead making a painting on canvas, I would have simply printed my photo to scale and make a graphite transfer of the drawing just the same.

It is not cheating to trace a photo of a model made by your own hands. It is still 100% your creation. Tracing this step is simply about efficiency. You will still need to modify those contours with details.

See also: Is It Cheating to Trace in Art?

At this point the process becomes typical – mixing the desired color and placing it in the right spot. The painting is 100% from imagination because the photo reference was a product of imagination.

Where did the Model Make a Difference?

Having the model made a difference in several ways. In my original gesture sketches, I only imagined the dragon from the front and side. The final pose was from above. Choosing such a dynamic orientation was a direct result of having a model to observe from many angles.

The model also made a difference in terms of accuracy. Without the model, the one wing may not have had such a specific fold. Even the horns would have been harder to figure out on paper than in clay, especially since one horn is foreshortened.

As mentioned before, the precarious composition is a direct result of observing the model. Without it I would not have ended up with the painting that I did.

The greatest benefit to this process for me is nailing the lighting. One short-coming I see in fantasy illustration is both a complexity of light and point of view. Without having built the model, I feel as though I might not have made such a bold choice with regards to the strong contrast in value or the unusual point of view. Pick up some modeling clay yourself and give 3D sketching a try.

If so, join over 36,000 others that receive our newsletter with new drawing and painting lessons. Plus, check out three of our course videos and ebooks for free.