We’ve all been taught throughout our lives there is one right answer to problems. There is the “correct” answer and then an infinite number of incorrect answers.

In math, “2 + 2” will always equal “4”. All other answers are wrong.

There is a solution – one solution – and everything else is wrong.

For the most part, we continue to train our students to think this way. We train them to respond with the correct answer – in the classroom and on the test. We tell them that there’s one answer and it can be found at the back of the book. These days, problem solving is no longer about the process, but more so about the answer.

Unfortunately, this has trained some of us to believe that art functions in the same way. Our years of schooling and experiences have forged a belief that there is one correct way to approach art creation and that all other ways are incorrect or somehow less successful.

Some of us spend years and even decades trying to find that one, elusive, correct way. Many others give up in frustration because the answer doesn’t come quickly or doesn’t seem attainable.

We have been trained to find answers based on formulas, so we search for one to improve our art. Formulas for drawing and painting can be useful, but these formulas do not always lead us on a path to art success. For some, formulas hinder and can be limiting. The path to success in creating art is more personal, more rewarding, and more ambiguous.

We can’t approach our art-making with the expectation that there is one right answer – one perfect solution for our subject with the medium of our choice. The one correct answer doesn’t exist. But what does exist is many correct answers – an infinite number of correct answers.

The artist doesn’t find the answer – he creates it.

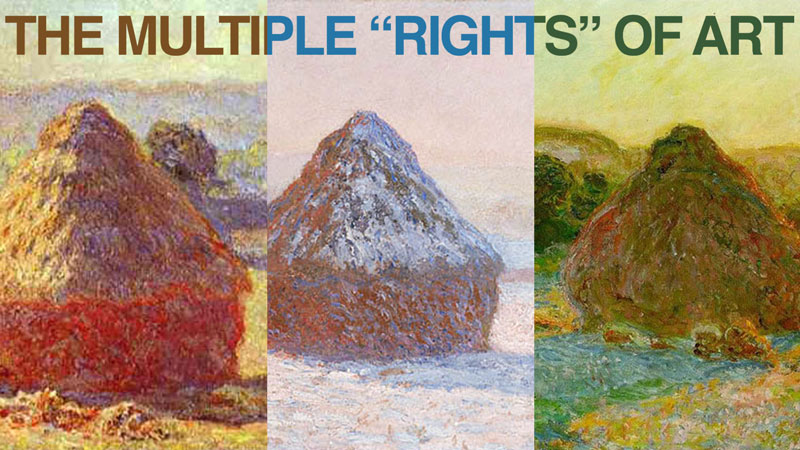

Monet’s Multiple Rights

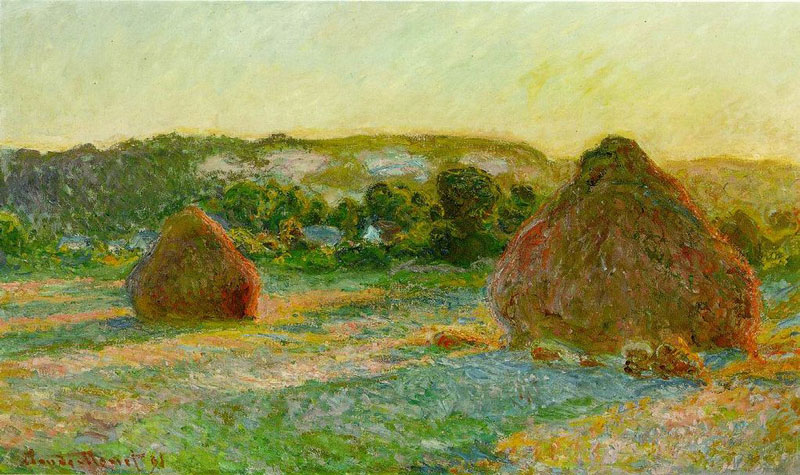

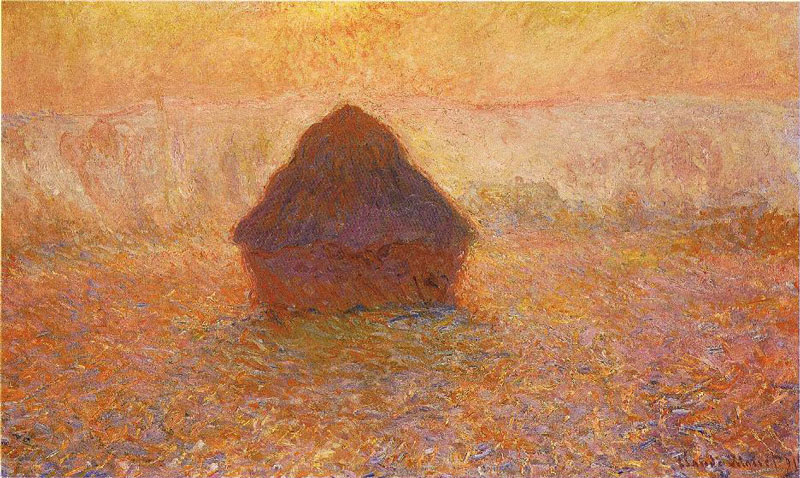

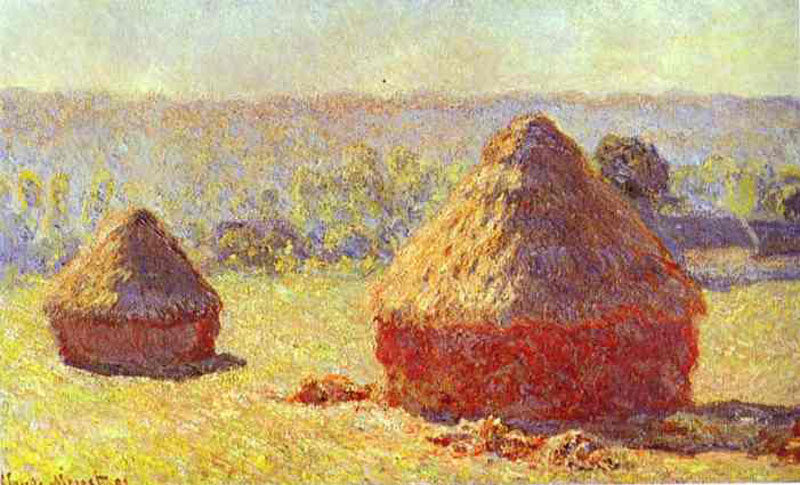

We need not look further than Monet’s Haystacks series as an example of “multiple rights”. Monet created a series of paintings of the same subject, haystacks, at different times of the day and different times of the year. The series of around 30 paintings was a study of light and season.

Some of the paintings are bright while others are solemn. The composition of each work is slightly different, but the subject stays the same.

Each painting is its own unique interpretation of the subject. Even though the same subject is depicted with the same medium, by the same artist, each painting stands on its own as a successful solution.

Monet was focused on capturing the light and the subtle nuances of color that resulted. He often continued to work on the paintings in his studio after beginning them in the field, pulling out colors and harmonizing his palette.

Each of the paintings is an answer – an answer to the same question. Each painting is a correct response – a right answer.

We should also be free to create without restriction or apprehension of being wrong. We should make each stroke of the brush without fear of “messing up”. Each mark that we make should be made with confidence knowing that what we create is our answer – our unique, correct response.

Skill and Artistic Voice

Just as there are many paths to the same destination, there are many ways an artist can arrive at a solution in a drawing or painting. And just as a vehicle is often required to carry a passenger to a destination, skill is required to carry an artist to their solution.

Drawing and painting skills are required. Craftsmanship is important. This is different from our unique artistic voice – the one that we speak with when we present our solution in a work of art. Skill is what we use to speak through.

Therefore, we should continue to develop our skills so that we may speak more eloquently through the works that we create and the answers that we offer.

Monet worked tirelessly on manipulating the colors in his paintings and the spontaneity of his brush strokes. He worked to develop his skills with a demanding eye for perfection so that his solutions were as complete as possible.

Monet could not manipulate color without a knowledge of color theory. He could not paint with a level of mastery without a knowledge of the medium that he used.

We too should approach our art in the same manner. We should not compromise and present an answer void of skill. Instead, we should put ourselves in a constant state of improvement and betterment, learning as much as we can and crafting our skills as we learn.

As we learn, grow, and continue to develop our skills, we should accept the answers (the artworks) that we create along the way as our “correct” answer at the time – the one that fit the moment.

We should stop looking for the “correct” answer and instead begin looking for our answer. Our skills will be at different levels at different times, but the answers that we present can all the right ones.

If so, join over 36,000 others that receive our newsletter with new drawing and painting lessons. Plus, check out three of our course videos and ebooks for free.